Evolution of the arts

The evolution of the arts has been my main research focus for the last several years.

I consider the evolutionary approach to be complementary to traditional approaches. If carefully used, I believe it offers a rich variety of invaluable insights as well as exciting new avenues for research.

Following questions I have addressed in my work:

Are the arts adaptations and if so what functions did/do they serve? What are the relative contributions of genes and culture to their emergence and persistence? What can artlike behaviors of nonhuman animals tell us about the evolution of art in the human lineage? Can an evolutionary approach elucidate processes occurring in highly specialized contemporary art worlds?

In reverse chronological order, here are academic papers I published on this topic.

Verpooten, J., & Eens, M. (2021). Singing is not associated with social complexity across species. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Abstract

Based on their social bonding hypothesis, Savage et al. predict a relation between ‘musical’ behaviors and social complexity across species. However, our qualitative comparative review suggests that, while learned contact calls are positively associated with complex social dynamics across species, songs are not. Yet, in contrast to songs, and arguably consistent with their functions, contact calls are not particularly music-like.

Verpooten, J. (2021). Complex vocal learning and three-dimensional mating environments. Biology & Philosophy. doi.org/10.1007/s10539-021-09786-2

Abstract

Complex vocal learning, the capacity to imitate new sounds, underpins the evolution of animal vocal cultures and song dialects and is a key prerequisite for human speech and song. Due to its relevance for the understanding of cultural evolution and the biology and evolution of language and music, the trait has gained much scholarly attention. However, while we have seen tremendous progress with respect to our understanding of its morphological, neurological and genetic aspects, its peculiar phylogenetic distribution has remained elusive. Intriguingly, animals as distinct as hummingbirds and humpback whales share well-developed vocal learning capacity in common with humans, while this ability is quite limited in nonhuman primates. Yet, solving this ‘vocal learning conundrum’ may shed light on the constraints ancestral humans overcame to unleash their vocal capacities. To this end I consider major constraints and functions that have been proposed. I highlight an especially promising ecological constraint, namely the spatial dimensionality of the environment. Based on an informal comparative review, I suggest that complex vocal learning is associated with three-dimensional habitats such as air and water. I argue that this is consistent with recent theoretical advances—i.e., the coercion-avoidance and dimensionality hypotheses—and with the long-standing hypothesis that mate choice is a major driver of the evolution and origin of complex vocal learning. However, I stress that multiple functions may apply and that quantitative phylogenetic comparative methods should be employed to finally resolve the issue.

De Tiège, A., Verpooten, J., & Braeckman, J. (2021). From animal signals to art: Manipulative animal signaling and the evolutionary foundations of aesthetic behavior and art production. Quarterly Review of Biology. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/713210

Abstract

As humans are evolved animals, we propose a nonanthropocentric framework based on animal signaling theory to understand the evolutionary foundations of human art, instead of a classical anthropocentric approach based on sociocultural anthropology that may incorporate evolutionary thinking but does not start with it. First, we provide a concise review of the basics of the evolutionary theory of animal communication or signaling. Second, we apply this theory to specifically human aesthetic behavior and art and provide four empirical arguments or factors that reduce the conceptual gap between nonhuman animal signaling and human aesthetic-artistic behavior (two from the nonhuman and two from the human side) and that, as such, grant an implementation of human aesthetic behavior and art production within animal signaling theory. And, third, we explore the theory’s explanatory power and value when applied to aesthetic behavior and art production through proposing four valuable insights or hypotheses that it may contribute or generate: on art’s operation within multiple functionally adaptive signaling contexts; on the basic evolutionary economics of art or what art is (for); on why art is functionally adaptive rather than a nonfunctional byproduct; and on how art is functionally rooted in competitive-manipulative animal signaling and—unlike language—only to a lesser extent in cooperative-informative signaling. Overall, animal signaling theory offers a potentially integrating account of the arts because humans and their signaling behaviors are conceptually situated within a broader, transhuman field that also comprises nonhuman species and their behaviors, thus allowing for an identification of deeper commonalities (homologs, analogs) as well as unique differences. As such, we hope to increase insights into how acoustic, gestural/postural, visual, olfactory, and gustatory animal signaling evolved into music, dance, visual art, perfumery, and gastronomy, respectively.

Verpooten J (2020). RICHARD O. PRUM, The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin's Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World—and Us. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences (313) DOI: 10.1007/s40656-020-00313-2

LINK

In this book, Richard Prum, Yale professor in evolutionary ornithology, defends a theory of sexual selection in which the act of choosing a mate for purely aesthetic reasons - for the mere pleasure of it - is an independent engine of evolutionary change. Dubbing this process ‘arbitrary coevolution’ or ‘beauty happens’, Prum pits it against the good genes model of sexual selection through mate choice. The first two thirds of the book provide an in-depth theoretical discussion of these two models of sexual selection by way of comprehensive, up-to-date review of the biological literature on fascinating sexual displays and life of birds such as ducks, bowerbirds and neotropical manakins. Shifting his attention to humans in the final third of the book, he explores how his theory may explain a variety of traits such as the female orgasm (and the intensity of the male orgasm) or ‘pleasure happens’, reduced physical weaponry of men in comparison to other great apes or ‘aesthetic deweaponization’, and the evolution of same-sex behavior or the ‘queering of Homo sapiens’. The book has received a fair bit of media attention and was a 2018 Pulitzer prize finalist and named a best book of the year by the New York Times book review, Smithsonian, and Wall Street Journal. This should not come as a surprise as Prum delivers a skillfully crafted account that is provocative, engaging, funny and at the same time informative. However, academic reception, especially from colleague biologists working in the domain of sexual selection, has been more critical. Prum’s colleagues mainly take issue with two fundamental aspects of the book. Concerns have been raised regarding the dichotomy he presents between his ‘arbitrary coevolution’ theory and good genes, on the one hand, and the portrayal of evolutionary biologists’ and psychologists’ underlying preferences and ideological biases, which, purportedly, lead them to favor good genes, on the other.

Verpooten J (2018). Expertise affects aesthetic evolution. Evidence from artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments. In: Kapoula, Z., Volle, E., Renoult, J., Andreatta, M (eds) Exploring Transdisciplinarity in Art and Science, Art, Aesthetics, Creativity and Science book series, Springer.

Link

Abstract

An unmade bed. A cigarette glued to the wall. A replica of a soup can box. Drippings on a canvas. Can an evolutionary approach help us understand the production and appreciation of, sometimes perplexing, modern and contemporary art? This chapter attempts at this by investigating two hypotheses about the evolution of human aesthetics in the domain of art. The first hypothesis, commonly called evolutionary aesthetics, asserts that aesthetic preferences, such as those for particular faces, body shapes and animals, have evolved in our ancestors because they motivated adaptive behavior. Artworks (e.g., those depicting facial beauty) may exploit these ancestral aesthetic preferences. In contrast, the second hypothesis states that aesthetic preferences continuously coevolve with artworks, and that they are subject to learning from, especially prestigious, other individuals. We called this mechanism prestige driven coevolutionary aesthetics. Here I report artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments we conducted. We found that while exploitation of ancestral aesthetic preferences prevails among non-experts, prestige driven coevolutionary aesthetics dominates expert appreciation. I speculate that the latter mechanism can explain modern and contemporary art’s deviations from evolutionary aesthetics as well as the existence and persistence of its elusiveness. I also discuss the potential relevance of our findings to major fields studying aesthetics, that is, empirical aesthetics, and sociological and historical approaches to art.

Verpooten J, Dewitte S (2017) The Conundrum Of Modern Art: Prestige Driven Coevolutionary Aesthetics Trumps Evolutionary Aesthetics Among Art Experts. Human Nature 28, 1, 16–38.

featured in the press: Psypost / NYMag / Forbes / ArtNews / The Art Market Monitor

Link

Abstract

Two major mechanisms of aesthetic evolution have been suggested. One focuses on naturally selected preferences (Evolutionary Aesthetics), while the other describes a process of evaluative coevolution whereby preferences coevolve with signals. Signaling theory suggests that expertise moderates these mechanisms. In this article we set out to verify this hypothesis in the domain of art and use it to elucidate Western modern art’s deviation from naturally selected preferences. We argue that this deviation is consistent with a Coevolutionary Aesthetics mechanism driven by prestige-biased social learning among art experts. In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted two studies in which we assessed the effects on lay and expert appreciation of both the biological relevance of the given artwork’s depicted content, viz., facial beauty, and the prestige specific to the artwork’s associated context (MoMA). We found that laypeople appreciate artworks based on their depictions of facial beauty, mediated by aesthetic pleasure, which is consistent with previous studies. In contrast, experts appreciate the artworks based on the prestige of the associated context, mediated by admiration for the artist. Moreover, experts appreciate artworks depicting neutral faces to a greater degree than artworks depicting attractive faces. These findings thus corroborate our contention that expertise moderates the Evolutionary and Coevolutionary Aesthetics mechanisms in the art domain. Furthermore, our findings provide initial support for our proposal that prestige-driven coevolution with expert evaluations plays a decisive role in modern art’s deviation from naturally selected preferences. After discussing the limitations of our research as well as the relation that our results bear on cultural evolution theory, we provide a number of suggestions for further research into the potential functions of expert appreciation that deviates from naturally selected preferences, on the one hand, and expertise as a moderator of these mechanisms in other cultural domains, on the other.

Hodgson D, Verpooten J (2015) The Evolutionary Significance of the Arts: Exploring the Byproduct Hypothesis in the Context of Ritual, Precursors, and Cultural Evolution. Biological Theory 10, 1, 73-85.

Link

Abstract

The role of the arts has become crucial to understanding the origins of ‘‘modern human behavior,’’ but continues to be highly controversial as it is not always clear why the arts evolved and persisted. This issue is often addressed by appealing to adaptive biological explanations. However, we will argue that the arts have evolved culturally rather than biologically, exploiting biological adaptations rather than extending them. In order to support this line of inquiry, evidence from a number of disciplines will be presented showing how the relationship between the arts, evolution, and adaptation can be better understood by regarding cultural transmission as an important second inheritance system. This will allow an alternative proposal to be formulated as to the proper place of the arts in human evolution. However, in order for the role of the arts to be fully addressed, the relationship of culture to genes and adaptation will be explored. Based on an assessment of the cognitive, biological, and cultural aspects of the arts, and their close relationship with ritual and associated activities, we will conclude with the null hypothesis that the arts evolved as a necessary but nonfunctional concomitant of other traits that cannot currently be refuted.

Verpooten J (2013) Extending Literary Darwinism: culture and alternatives to adaptation. Scientific Studies of Literature 3 (1): 19-27.

Link

Abstract

Literary Darwinism is an emerging interdisciplinary research field that seeks to explain literature and its oral antecedents (“literary behaviors”), from a Darwinian perspective. Considered the fact that an evolutionary approach to human behavior has proven insightful, this is a promising endeavor. However, Literary Darwinism as it is commonly practiced, I argue, suffers from some shortcomings. First, while literary Darwinists only weigh adaptation against by-product as competing explanations of literary behaviors, other alternatives, such as constraint and exaptation, should be considered as well. I attempt to demonstrate their relevance by evaluating the evidentiary criteria commonly employed by Literary Darwinists. Second, Literary Darwinists usually acknowledge the role of culture in human behavior and make references to Dual Inheritance theory (i.e., the body of empirical and theoretical work demonstrating that human behavior is the outcome of both genetic and cultural inheritance). However, they often do not fully appreciate the explanatory implications of dual inheritance. Literary Darwinism should be extended to include recent refinements in our understanding of the evolution of human behavior.

Verpooten J (2012) Brian Boyd's Evolutionary Account of Art: Fiction or Future? Biological Theory, 6, 2, 176-183

Link

Abstract

There has been a recent surge of evolutionary explanations of art. In this article I evaluate one currently influential example, Brian Boyd’s recent book On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (2009). The book offers a stimulating collection of findings, ideas, and hypotheses borrowed from a wide range of research disciplines (philosophy of art and art criticism, anthropology, evolutionary and developmental psychology, neurobiology, ethology, etc.), brought together under the umbrella of evolution. However, in so doing Boyd lumps together issues that need to be separated, most importantly, organic and cultural evolution. In addition, he fails to consider alternative explanations to art as adaptation such as exaptation and constraint. Moreover, the neurobiological literature suggests current evidence of biological adaptation for most of the arts is weak at best. Given these considerations, I conclude by proposing to regard the arts instead as culturally evolved practices building on pre-existing biological traits.

Verpooten J, Nelissen M (2012) Sensory exploitation: underestimated in the evolution of art as once in sexual selection? In: Plaisance KS, Reydon TAC (eds) Philosophy of Behavioral Biology, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 282, 4, 189-216

Link

Verpooten J, Nelissen M (2010) Sensory exploitation and cultural transmission: the late emergence of iconic representations in human evolution. Theory in Biosciences 129 (2-3): 211 - 221.

Link

Abstract

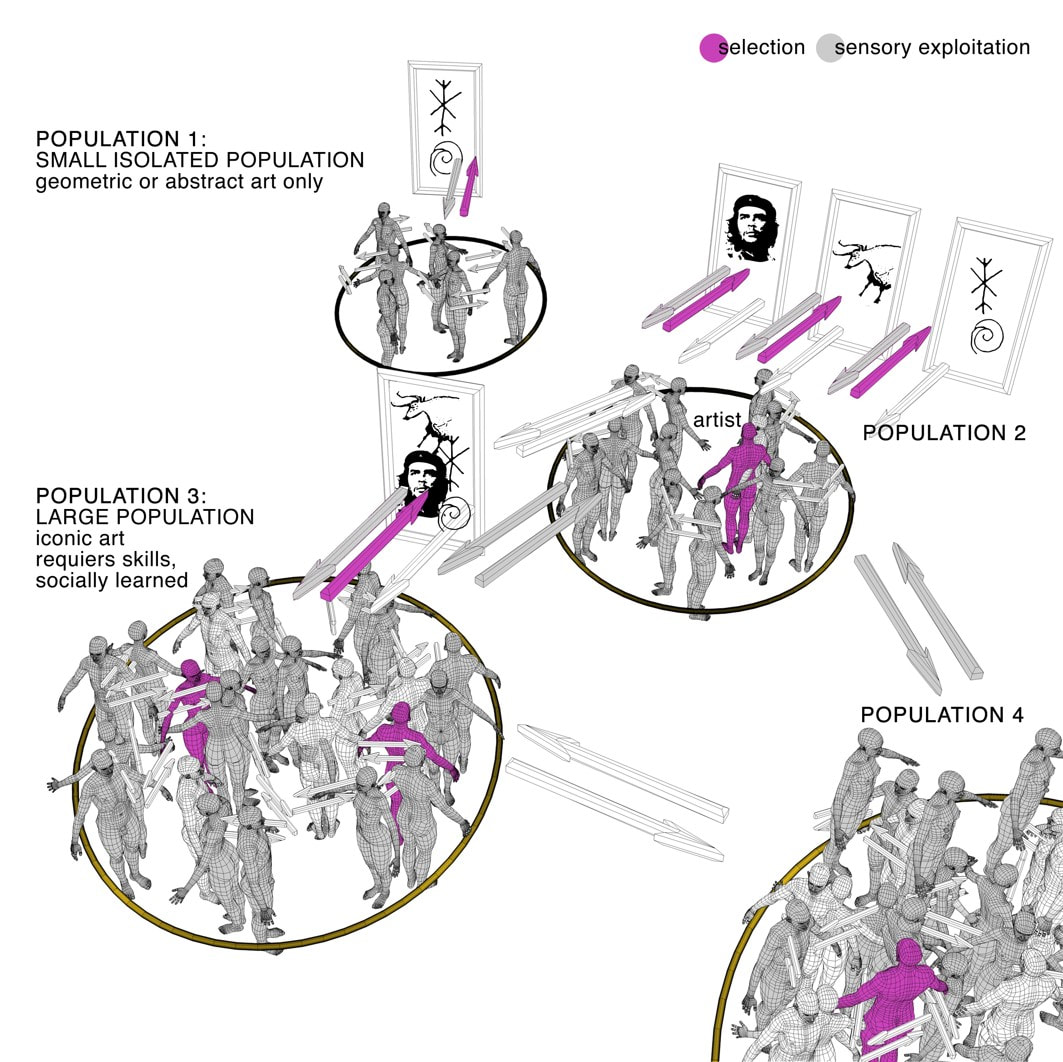

We address a conundrum that has puzzled archeologists and art historians (Spivey, 2005): the lag between the rise of anatomically modern humans about 200,000–160,000 years ago and complex art (i.e., figurative imagery and realistic art), which only appeared consistently in the archaeological record about 45,000 years ago. The dominant explanation of this lag has been that due to some assumed genetic mutations a neurocognitive change took place, which led to a creative explosion (in Europe). Recently, insights from cultural evolution theory have allowed formulating an alternative explanation that better fits existing data. One of these data is that realistic art appeared (and disappeared) not only in Europe but in several parts of the world since the Upper Paleolithic / Late Stone Age. Essentially, it seems that the accumulation and retention of innovations required for producing complex artefacts, such as realistic depictions (e.g., learned aspects of drawing skills, pigment processing, charting suitable surfaces, etc.) necessitate a large enough population of socially interacting individuals. Evidence indicates such a demographic change took place in Upper Paleolithic Europe prior to the appearance of figurative cave art, thus providing an alternative explanation for the creative explosion. Existing models assume that socially learned complex behaviors including art making were retained for adaptive purposes (Powell et al., 2009). However, in this chapter, we provide an alternative, more parsimonious (in the relative sense: Sober, 2006), explanation. We propose that art evolved because it exploited preexisting preferences, that were maintained by selection in another context (e.g., face recognition system in the brain exploited by portraits). On this view, figurative art traditions have evolved by piggybacking on cumulative adaptive evolution. We conclude that sensory exploitation is a “primary force” that suffices to drive the evolution of art, but that, depending on identifiable conditions (see discussion Appendix 2), secondary forces may kick in.

I consider the evolutionary approach to be complementary to traditional approaches. If carefully used, I believe it offers a rich variety of invaluable insights as well as exciting new avenues for research.

Following questions I have addressed in my work:

Are the arts adaptations and if so what functions did/do they serve? What are the relative contributions of genes and culture to their emergence and persistence? What can artlike behaviors of nonhuman animals tell us about the evolution of art in the human lineage? Can an evolutionary approach elucidate processes occurring in highly specialized contemporary art worlds?

In reverse chronological order, here are academic papers I published on this topic.

Verpooten, J., & Eens, M. (2021). Singing is not associated with social complexity across species. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Abstract

Based on their social bonding hypothesis, Savage et al. predict a relation between ‘musical’ behaviors and social complexity across species. However, our qualitative comparative review suggests that, while learned contact calls are positively associated with complex social dynamics across species, songs are not. Yet, in contrast to songs, and arguably consistent with their functions, contact calls are not particularly music-like.

Verpooten, J. (2021). Complex vocal learning and three-dimensional mating environments. Biology & Philosophy. doi.org/10.1007/s10539-021-09786-2

Abstract

Complex vocal learning, the capacity to imitate new sounds, underpins the evolution of animal vocal cultures and song dialects and is a key prerequisite for human speech and song. Due to its relevance for the understanding of cultural evolution and the biology and evolution of language and music, the trait has gained much scholarly attention. However, while we have seen tremendous progress with respect to our understanding of its morphological, neurological and genetic aspects, its peculiar phylogenetic distribution has remained elusive. Intriguingly, animals as distinct as hummingbirds and humpback whales share well-developed vocal learning capacity in common with humans, while this ability is quite limited in nonhuman primates. Yet, solving this ‘vocal learning conundrum’ may shed light on the constraints ancestral humans overcame to unleash their vocal capacities. To this end I consider major constraints and functions that have been proposed. I highlight an especially promising ecological constraint, namely the spatial dimensionality of the environment. Based on an informal comparative review, I suggest that complex vocal learning is associated with three-dimensional habitats such as air and water. I argue that this is consistent with recent theoretical advances—i.e., the coercion-avoidance and dimensionality hypotheses—and with the long-standing hypothesis that mate choice is a major driver of the evolution and origin of complex vocal learning. However, I stress that multiple functions may apply and that quantitative phylogenetic comparative methods should be employed to finally resolve the issue.

De Tiège, A., Verpooten, J., & Braeckman, J. (2021). From animal signals to art: Manipulative animal signaling and the evolutionary foundations of aesthetic behavior and art production. Quarterly Review of Biology. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/713210

Abstract

As humans are evolved animals, we propose a nonanthropocentric framework based on animal signaling theory to understand the evolutionary foundations of human art, instead of a classical anthropocentric approach based on sociocultural anthropology that may incorporate evolutionary thinking but does not start with it. First, we provide a concise review of the basics of the evolutionary theory of animal communication or signaling. Second, we apply this theory to specifically human aesthetic behavior and art and provide four empirical arguments or factors that reduce the conceptual gap between nonhuman animal signaling and human aesthetic-artistic behavior (two from the nonhuman and two from the human side) and that, as such, grant an implementation of human aesthetic behavior and art production within animal signaling theory. And, third, we explore the theory’s explanatory power and value when applied to aesthetic behavior and art production through proposing four valuable insights or hypotheses that it may contribute or generate: on art’s operation within multiple functionally adaptive signaling contexts; on the basic evolutionary economics of art or what art is (for); on why art is functionally adaptive rather than a nonfunctional byproduct; and on how art is functionally rooted in competitive-manipulative animal signaling and—unlike language—only to a lesser extent in cooperative-informative signaling. Overall, animal signaling theory offers a potentially integrating account of the arts because humans and their signaling behaviors are conceptually situated within a broader, transhuman field that also comprises nonhuman species and their behaviors, thus allowing for an identification of deeper commonalities (homologs, analogs) as well as unique differences. As such, we hope to increase insights into how acoustic, gestural/postural, visual, olfactory, and gustatory animal signaling evolved into music, dance, visual art, perfumery, and gastronomy, respectively.

Verpooten J (2020). RICHARD O. PRUM, The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin's Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World—and Us. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences (313) DOI: 10.1007/s40656-020-00313-2

LINK

In this book, Richard Prum, Yale professor in evolutionary ornithology, defends a theory of sexual selection in which the act of choosing a mate for purely aesthetic reasons - for the mere pleasure of it - is an independent engine of evolutionary change. Dubbing this process ‘arbitrary coevolution’ or ‘beauty happens’, Prum pits it against the good genes model of sexual selection through mate choice. The first two thirds of the book provide an in-depth theoretical discussion of these two models of sexual selection by way of comprehensive, up-to-date review of the biological literature on fascinating sexual displays and life of birds such as ducks, bowerbirds and neotropical manakins. Shifting his attention to humans in the final third of the book, he explores how his theory may explain a variety of traits such as the female orgasm (and the intensity of the male orgasm) or ‘pleasure happens’, reduced physical weaponry of men in comparison to other great apes or ‘aesthetic deweaponization’, and the evolution of same-sex behavior or the ‘queering of Homo sapiens’. The book has received a fair bit of media attention and was a 2018 Pulitzer prize finalist and named a best book of the year by the New York Times book review, Smithsonian, and Wall Street Journal. This should not come as a surprise as Prum delivers a skillfully crafted account that is provocative, engaging, funny and at the same time informative. However, academic reception, especially from colleague biologists working in the domain of sexual selection, has been more critical. Prum’s colleagues mainly take issue with two fundamental aspects of the book. Concerns have been raised regarding the dichotomy he presents between his ‘arbitrary coevolution’ theory and good genes, on the one hand, and the portrayal of evolutionary biologists’ and psychologists’ underlying preferences and ideological biases, which, purportedly, lead them to favor good genes, on the other.

Verpooten J (2018). Expertise affects aesthetic evolution. Evidence from artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments. In: Kapoula, Z., Volle, E., Renoult, J., Andreatta, M (eds) Exploring Transdisciplinarity in Art and Science, Art, Aesthetics, Creativity and Science book series, Springer.

Link

Abstract

An unmade bed. A cigarette glued to the wall. A replica of a soup can box. Drippings on a canvas. Can an evolutionary approach help us understand the production and appreciation of, sometimes perplexing, modern and contemporary art? This chapter attempts at this by investigating two hypotheses about the evolution of human aesthetics in the domain of art. The first hypothesis, commonly called evolutionary aesthetics, asserts that aesthetic preferences, such as those for particular faces, body shapes and animals, have evolved in our ancestors because they motivated adaptive behavior. Artworks (e.g., those depicting facial beauty) may exploit these ancestral aesthetic preferences. In contrast, the second hypothesis states that aesthetic preferences continuously coevolve with artworks, and that they are subject to learning from, especially prestigious, other individuals. We called this mechanism prestige driven coevolutionary aesthetics. Here I report artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments we conducted. We found that while exploitation of ancestral aesthetic preferences prevails among non-experts, prestige driven coevolutionary aesthetics dominates expert appreciation. I speculate that the latter mechanism can explain modern and contemporary art’s deviations from evolutionary aesthetics as well as the existence and persistence of its elusiveness. I also discuss the potential relevance of our findings to major fields studying aesthetics, that is, empirical aesthetics, and sociological and historical approaches to art.

Verpooten J, Dewitte S (2017) The Conundrum Of Modern Art: Prestige Driven Coevolutionary Aesthetics Trumps Evolutionary Aesthetics Among Art Experts. Human Nature 28, 1, 16–38.

featured in the press: Psypost / NYMag / Forbes / ArtNews / The Art Market Monitor

Link

Abstract

Two major mechanisms of aesthetic evolution have been suggested. One focuses on naturally selected preferences (Evolutionary Aesthetics), while the other describes a process of evaluative coevolution whereby preferences coevolve with signals. Signaling theory suggests that expertise moderates these mechanisms. In this article we set out to verify this hypothesis in the domain of art and use it to elucidate Western modern art’s deviation from naturally selected preferences. We argue that this deviation is consistent with a Coevolutionary Aesthetics mechanism driven by prestige-biased social learning among art experts. In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted two studies in which we assessed the effects on lay and expert appreciation of both the biological relevance of the given artwork’s depicted content, viz., facial beauty, and the prestige specific to the artwork’s associated context (MoMA). We found that laypeople appreciate artworks based on their depictions of facial beauty, mediated by aesthetic pleasure, which is consistent with previous studies. In contrast, experts appreciate the artworks based on the prestige of the associated context, mediated by admiration for the artist. Moreover, experts appreciate artworks depicting neutral faces to a greater degree than artworks depicting attractive faces. These findings thus corroborate our contention that expertise moderates the Evolutionary and Coevolutionary Aesthetics mechanisms in the art domain. Furthermore, our findings provide initial support for our proposal that prestige-driven coevolution with expert evaluations plays a decisive role in modern art’s deviation from naturally selected preferences. After discussing the limitations of our research as well as the relation that our results bear on cultural evolution theory, we provide a number of suggestions for further research into the potential functions of expert appreciation that deviates from naturally selected preferences, on the one hand, and expertise as a moderator of these mechanisms in other cultural domains, on the other.

Hodgson D, Verpooten J (2015) The Evolutionary Significance of the Arts: Exploring the Byproduct Hypothesis in the Context of Ritual, Precursors, and Cultural Evolution. Biological Theory 10, 1, 73-85.

Link

Abstract

The role of the arts has become crucial to understanding the origins of ‘‘modern human behavior,’’ but continues to be highly controversial as it is not always clear why the arts evolved and persisted. This issue is often addressed by appealing to adaptive biological explanations. However, we will argue that the arts have evolved culturally rather than biologically, exploiting biological adaptations rather than extending them. In order to support this line of inquiry, evidence from a number of disciplines will be presented showing how the relationship between the arts, evolution, and adaptation can be better understood by regarding cultural transmission as an important second inheritance system. This will allow an alternative proposal to be formulated as to the proper place of the arts in human evolution. However, in order for the role of the arts to be fully addressed, the relationship of culture to genes and adaptation will be explored. Based on an assessment of the cognitive, biological, and cultural aspects of the arts, and their close relationship with ritual and associated activities, we will conclude with the null hypothesis that the arts evolved as a necessary but nonfunctional concomitant of other traits that cannot currently be refuted.

Verpooten J (2013) Extending Literary Darwinism: culture and alternatives to adaptation. Scientific Studies of Literature 3 (1): 19-27.

Link

Abstract

Literary Darwinism is an emerging interdisciplinary research field that seeks to explain literature and its oral antecedents (“literary behaviors”), from a Darwinian perspective. Considered the fact that an evolutionary approach to human behavior has proven insightful, this is a promising endeavor. However, Literary Darwinism as it is commonly practiced, I argue, suffers from some shortcomings. First, while literary Darwinists only weigh adaptation against by-product as competing explanations of literary behaviors, other alternatives, such as constraint and exaptation, should be considered as well. I attempt to demonstrate their relevance by evaluating the evidentiary criteria commonly employed by Literary Darwinists. Second, Literary Darwinists usually acknowledge the role of culture in human behavior and make references to Dual Inheritance theory (i.e., the body of empirical and theoretical work demonstrating that human behavior is the outcome of both genetic and cultural inheritance). However, they often do not fully appreciate the explanatory implications of dual inheritance. Literary Darwinism should be extended to include recent refinements in our understanding of the evolution of human behavior.

Verpooten J (2012) Brian Boyd's Evolutionary Account of Art: Fiction or Future? Biological Theory, 6, 2, 176-183

Link

Abstract

There has been a recent surge of evolutionary explanations of art. In this article I evaluate one currently influential example, Brian Boyd’s recent book On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (2009). The book offers a stimulating collection of findings, ideas, and hypotheses borrowed from a wide range of research disciplines (philosophy of art and art criticism, anthropology, evolutionary and developmental psychology, neurobiology, ethology, etc.), brought together under the umbrella of evolution. However, in so doing Boyd lumps together issues that need to be separated, most importantly, organic and cultural evolution. In addition, he fails to consider alternative explanations to art as adaptation such as exaptation and constraint. Moreover, the neurobiological literature suggests current evidence of biological adaptation for most of the arts is weak at best. Given these considerations, I conclude by proposing to regard the arts instead as culturally evolved practices building on pre-existing biological traits.

Verpooten J, Nelissen M (2012) Sensory exploitation: underestimated in the evolution of art as once in sexual selection? In: Plaisance KS, Reydon TAC (eds) Philosophy of Behavioral Biology, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 282, 4, 189-216

Link

Verpooten J, Nelissen M (2010) Sensory exploitation and cultural transmission: the late emergence of iconic representations in human evolution. Theory in Biosciences 129 (2-3): 211 - 221.

Link

Abstract

We address a conundrum that has puzzled archeologists and art historians (Spivey, 2005): the lag between the rise of anatomically modern humans about 200,000–160,000 years ago and complex art (i.e., figurative imagery and realistic art), which only appeared consistently in the archaeological record about 45,000 years ago. The dominant explanation of this lag has been that due to some assumed genetic mutations a neurocognitive change took place, which led to a creative explosion (in Europe). Recently, insights from cultural evolution theory have allowed formulating an alternative explanation that better fits existing data. One of these data is that realistic art appeared (and disappeared) not only in Europe but in several parts of the world since the Upper Paleolithic / Late Stone Age. Essentially, it seems that the accumulation and retention of innovations required for producing complex artefacts, such as realistic depictions (e.g., learned aspects of drawing skills, pigment processing, charting suitable surfaces, etc.) necessitate a large enough population of socially interacting individuals. Evidence indicates such a demographic change took place in Upper Paleolithic Europe prior to the appearance of figurative cave art, thus providing an alternative explanation for the creative explosion. Existing models assume that socially learned complex behaviors including art making were retained for adaptive purposes (Powell et al., 2009). However, in this chapter, we provide an alternative, more parsimonious (in the relative sense: Sober, 2006), explanation. We propose that art evolved because it exploited preexisting preferences, that were maintained by selection in another context (e.g., face recognition system in the brain exploited by portraits). On this view, figurative art traditions have evolved by piggybacking on cumulative adaptive evolution. We conclude that sensory exploitation is a “primary force” that suffices to drive the evolution of art, but that, depending on identifiable conditions (see discussion Appendix 2), secondary forces may kick in.

Architecture from an Evolutionary Perspective

How can Darwin's theory of evolution contribute to our understanding of architecture? Yannick Joye, who specializes on this topic from an environmental psychology perspective, and I co-authored a couple of papers that address aspects of architecture from a Darwinian perspective. We looked at monumentality and its link to religion, building behavior across species, signaling purposes of architectural aesthetics, and the role of cultural evolution.

Verpooten J, Joye Y (2014) Evolutionary interactions between human biology and architecture: insights from signaling theory and a cross-species comparative approach. In: Csibra G, Richerson P, Pléh C (eds) Naturalistic Approaches to Culture. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 201 - 221.

Link

Abstract

Rather than being a recently invented practice, building homes and other architectural constructions, such as temples and monuments, are a perennial part of the human behavioral repertoire, which may have had an important impact on human cultural, genetic, and ecological evolution. Studying architecture from a biological and evolutionary perspective may thus be relevant to the understanding of human evolution; and vice versa, a biological and evolutionary perspective may enhance our understanding of architecture as a crucial part of human life. Yet, human architecture has hardly been investigated from a biological and evolutionary perspective. In this chapter, we aim to contribute to this much-needed approach to architecture. First, we investigate the evolution of human building aptitudes from a phylogenetic perspective. Then, we address the evolution of aesthetic aspects of architecture and its eventual signaling purposes from a comparative perspective relying on models from signaling theory.

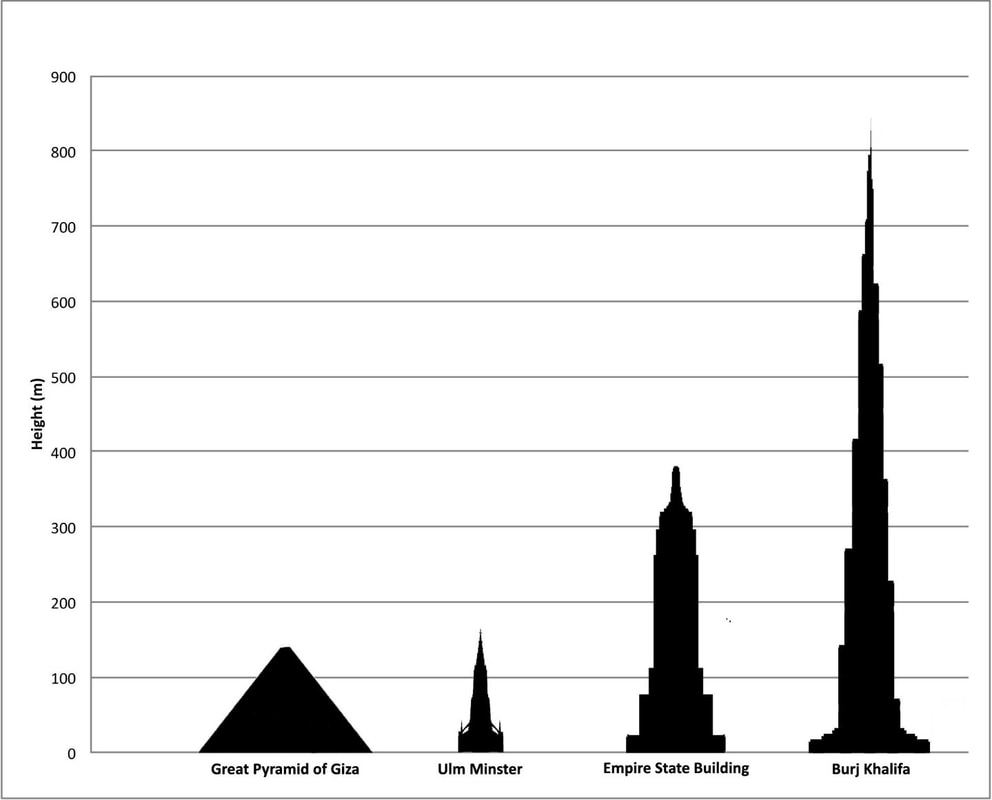

Joye Y, Verpooten J (2013) An exploration of the functions of religious monumental architecture from a Darwinian perspective. Review of General Psychology, 53-68.

Link

Abstract

In recent years, the cognitive science of religion has displayed a keen interest in religions’ social function, bolstering research on religious prosociality and cooperativeness. The main objective of this article is to explore, from a Darwinian perspective, the biological and psychological mechanisms through which religious monumental architecture (RMA) might support that specific function. A frequently held view is that monumental architecture is a costly signal that served vertical social stratification in complex large-scale societies. In this paper we extend that view. We hypothesize that the function(s) of RMA cannot be fully appreciated from a costly signaling perspective alone, and invoke a complementary mechanism, namely sensory exploitation. We propose that, in addition to being a costly signal, RMA also often taps into an adaptive “sensitivity for bigness.” The central hypothesis of this paper is that when cases of RMA strongly stimulate that sensitivity, and when commoners become aware of the costly investments that are necessary to build RMA, then this may give rise to a particular emotional response, namely awe. We will try to demonstrate that, by exploiting awe, RMA promotes and regulates prosocial behavior among religious followers and creates in them an openness to adopt supernatural beliefs.

Verpooten J, Joye Y (2014) Evolutionary interactions between human biology and architecture: insights from signaling theory and a cross-species comparative approach. In: Csibra G, Richerson P, Pléh C (eds) Naturalistic Approaches to Culture. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 201 - 221.

Link

Abstract

Rather than being a recently invented practice, building homes and other architectural constructions, such as temples and monuments, are a perennial part of the human behavioral repertoire, which may have had an important impact on human cultural, genetic, and ecological evolution. Studying architecture from a biological and evolutionary perspective may thus be relevant to the understanding of human evolution; and vice versa, a biological and evolutionary perspective may enhance our understanding of architecture as a crucial part of human life. Yet, human architecture has hardly been investigated from a biological and evolutionary perspective. In this chapter, we aim to contribute to this much-needed approach to architecture. First, we investigate the evolution of human building aptitudes from a phylogenetic perspective. Then, we address the evolution of aesthetic aspects of architecture and its eventual signaling purposes from a comparative perspective relying on models from signaling theory.

Joye Y, Verpooten J (2013) An exploration of the functions of religious monumental architecture from a Darwinian perspective. Review of General Psychology, 53-68.

Link

Abstract

In recent years, the cognitive science of religion has displayed a keen interest in religions’ social function, bolstering research on religious prosociality and cooperativeness. The main objective of this article is to explore, from a Darwinian perspective, the biological and psychological mechanisms through which religious monumental architecture (RMA) might support that specific function. A frequently held view is that monumental architecture is a costly signal that served vertical social stratification in complex large-scale societies. In this paper we extend that view. We hypothesize that the function(s) of RMA cannot be fully appreciated from a costly signaling perspective alone, and invoke a complementary mechanism, namely sensory exploitation. We propose that, in addition to being a costly signal, RMA also often taps into an adaptive “sensitivity for bigness.” The central hypothesis of this paper is that when cases of RMA strongly stimulate that sensitivity, and when commoners become aware of the costly investments that are necessary to build RMA, then this may give rise to a particular emotional response, namely awe. We will try to demonstrate that, by exploiting awe, RMA promotes and regulates prosocial behavior among religious followers and creates in them an openness to adopt supernatural beliefs.

Art Observation Post

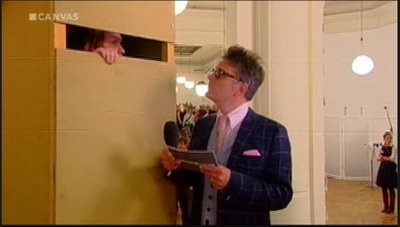

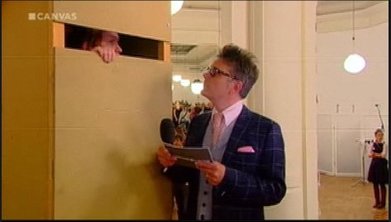

The Art Observation Post - AOP is a fibre board box in which an observer can take place to collect data on art event typical human behavior. My father, Gert Verpooten, designed and constructed it on the basis of my general instructions. Essentially, it had to be watertight and transportable, as I was going to use it for observations during the Kunstvlaai, an outdoor art fair in Amsterdam.

I sometimes use the AOP as an illustration in academic presentations. Once a biologist asked during the usual Q&A after the talk , "The observation posts that biologists use in the wild are camouflaged, so as not to disturb the animals' natural behavior. What about yours?" I said that my post was camouflaged as well, since I knew that my father would not never fall into the trap of trying to make something that looked poetic or aesthetic. "Double blind!" joked another biologist.

After having collected data on the art behavior of visitors at the Kunstvlaai art fair and at an exhibition (Extra [sic]), participation in the Canvascollectie, a national art contest, offered me an opportunity to collect data on the selection procedures typically employed in the art world.

This short video, shot by filmmaker Maaike Neuville, documents one stage of the selection procedure. It shows the jury assessing the AOP, while I am inside collecting data on their art assessment behaviors. This mutual assessment situation was reminiscent of stories of first contact between explorers and members of a previously isolated tribe. At least, I imagine that such encounters were also characterized by a blend of wonder and awkwardness.

I sometimes use the AOP as an illustration in academic presentations. Once a biologist asked during the usual Q&A after the talk , "The observation posts that biologists use in the wild are camouflaged, so as not to disturb the animals' natural behavior. What about yours?" I said that my post was camouflaged as well, since I knew that my father would not never fall into the trap of trying to make something that looked poetic or aesthetic. "Double blind!" joked another biologist.

After having collected data on the art behavior of visitors at the Kunstvlaai art fair and at an exhibition (Extra [sic]), participation in the Canvascollectie, a national art contest, offered me an opportunity to collect data on the selection procedures typically employed in the art world.

This short video, shot by filmmaker Maaike Neuville, documents one stage of the selection procedure. It shows the jury assessing the AOP, while I am inside collecting data on their art assessment behaviors. This mutual assessment situation was reminiscent of stories of first contact between explorers and members of a previously isolated tribe. At least, I imagine that such encounters were also characterized by a blend of wonder and awkwardness.

Despite the awkwardness, the jury selected the AOP for the final selection exhibition at BOZAR in Brussels. Because the exhibition was a three-week event, I needed some assistance and changing of the guard inside the post. Thus, I gave a crash course in observing behavior methods at the Monty art center and successfully recruited several assistants, mostly actresses - who, I have learned, know how to handle awkwardness .

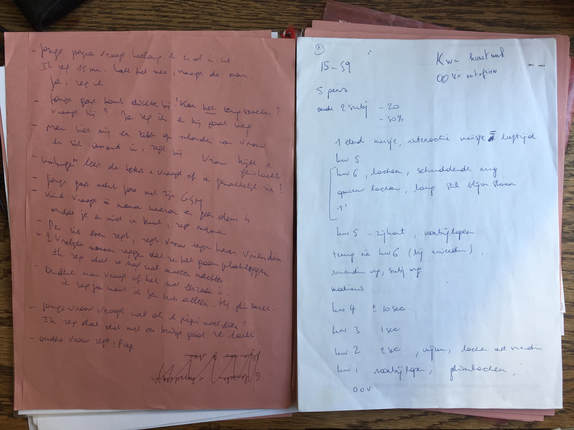

I gave them instructions on how to collect particular data but also encouraged them to perform ad libitum sampling, which boils down to recording whatever appears interesting. Here is an excerpt:

I gave them instructions on how to collect particular data but also encouraged them to perform ad libitum sampling, which boils down to recording whatever appears interesting. Here is an excerpt:

I am extremely grateful for their help.

The grand finale of the contest was being broadcast live on television. The organizers gauged my interest in giving an interview about the AOP. They also grilled me about my intentions with the AOP. Did I have artistic ambitions? I assured them that I did, because I wanted to get live on television. And so it happened.

Not long thereafter, the AOP was thrown away by workmen. It had been stored in the cellar of my apartment in a disassembled state and they had taken it for random rubbish. This time its camouflage had worked against it, unfortunately.

More info:

Verpooten J (2018). Expertise affects aesthetic evolution. Evidence from artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments. In: Kapoula, Z., Volle, E., Renoult, J., Andreatta, M (eds) Exploring Transdisciplinarity in Art and Science, Art, Aesthetics, Creativity and Science book series, Springer.

Link

The grand finale of the contest was being broadcast live on television. The organizers gauged my interest in giving an interview about the AOP. They also grilled me about my intentions with the AOP. Did I have artistic ambitions? I assured them that I did, because I wanted to get live on television. And so it happened.

Not long thereafter, the AOP was thrown away by workmen. It had been stored in the cellar of my apartment in a disassembled state and they had taken it for random rubbish. This time its camouflage had worked against it, unfortunately.

More info:

Verpooten J (2018). Expertise affects aesthetic evolution. Evidence from artistic fieldwork and psychological experiments. In: Kapoula, Z., Volle, E., Renoult, J., Andreatta, M (eds) Exploring Transdisciplinarity in Art and Science, Art, Aesthetics, Creativity and Science book series, Springer.

Link

Art of Biology projects

Artemia Choreography

Artemia aka brine shrimp aka Sea-Monkey aka Aqua Dragon are aquatic crustaceans found worldwide in inland saltwater lakes. They are widely sold alive as novelty gifts and fish food.

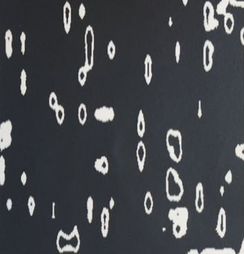

Hendrik-Jan Peeters and I created an installation that displayed their behaviors. On several occasions we projected their swirling swimming movements live on the walls of exhibition and festival spaces. Their elegant movements are not controlled through the brain but instead through local nervous system ganglia - only one of the fascinating facts about these creatures.

Hendrik-Jan Peeters and I created an installation that displayed their behaviors. On several occasions we projected their swirling swimming movements live on the walls of exhibition and festival spaces. Their elegant movements are not controlled through the brain but instead through local nervous system ganglia - only one of the fascinating facts about these creatures.

Materials: overhead projector, aquarium, Artemia, paper

Venues

"Will E.T. look like us?", soloshow, SALON2060, Antwerp, 2009

Ten Days On, festival, La Campine, Antwerp, 2010

Deurnroosje, festival, Deurne, 2010

Press

Gazet van Antwerpen, 2010, Dansende Pekelkreeftjes

Venues

"Will E.T. look like us?", soloshow, SALON2060, Antwerp, 2009

Ten Days On, festival, La Campine, Antwerp, 2010

Deurnroosje, festival, Deurne, 2010

Press

Gazet van Antwerpen, 2010, Dansende Pekelkreeftjes

Can humans and bowerbirds co-create a Superbower?

What shapes aesthetic and artlike behavior across species? The answers to this question are manifold. One neglected aspect, however, are the constraints imposed by environment and ecology, such as the risk of encountering or even attracting natural enemies and the local availability of materials.

The intended bio-art installation explores what happens when these constraints are artificially relaxed and the conditions for artlike behavior enhanced. Basically, a setting attuned to the needs of the animal is created where ample food is provided and biotic and abiotic threats are absent. Crucially, the conditions for the artlike behavior are intended to be artificially enhanced, so that it can flourish more than that it normally could in natural circumstances.

The purpose of the bio-art installation is to initiate a co-creation process between the animal and human spectators. For instance, in case the animal is a bowerbird, spectators are invited to present various objects to the bird, which it may or may not use to decorate its bower. This process is iterated and recorded, preferably in parallel and independently for several animals, although at some point interactions between individual animals might also be added to the mix, given that, for instance, bowerbirds tend to steal decorations from each other’s bowers. As Picasso is said to have said: “good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

How will the bowers look like?

Will individual bowerbirds of the same species tend to converge on similar characteristics of decorations, in terms of quantities, shapes, colors and so on, despite independent co-creation trajectories? Or will there be wide variability?

A possible outcome is that, once left unchecked by natural constraints, the bower will develop into a Superbower, consisting of decorations that are supernormally stimulating to the bird’s and perhaps the human beholder’s eyes.

ARTIFICIAL NATURE at Verbeke Foundation, Belgium

(cancelled my participation due to prep for fellowship at KLI in Austria)

Bio-art tentoonstelling 23 mei 2009 – 15 november 2009

Art Orienté objet (F), Sjoerd Buisman

(NL), Peter De Cupere (B), Marta de Menezes (P), Frederik De Wilde (B), Bart

de Zutter (B), Griet Dobbels (B), Jef Faes (B), Idiots (NL), Theo Jansen (NL),

Wout Janssens (B), Reinier Lagendijk (NL), Sjef Meijman (NL), Zjos Meyvis (B),

Desmond Morris (UK), NCNP (Ni Christi, Ni Politici) (B), Zbigniew Oksiuta (PL),

Raphaël Opstaele (B), Ingo Botho Reize (D), Joris Ribbens (B), Tineke

Schuurmans (NL), Lieven Standaert (B), STARTEL (NL), Martin uit den Bogaard

(NL), René Van Corven (NL), Ronald van der Meijs (NL), Philippe Vandenberg

(B), Maarten vanden Eynde (B), Koen Vanmechelen (B), Jan Verpooten (B),

Vadim Vosters (B), Stan Wannet (NL), Evelyne Wood (CH).

The intended bio-art installation explores what happens when these constraints are artificially relaxed and the conditions for artlike behavior enhanced. Basically, a setting attuned to the needs of the animal is created where ample food is provided and biotic and abiotic threats are absent. Crucially, the conditions for the artlike behavior are intended to be artificially enhanced, so that it can flourish more than that it normally could in natural circumstances.

The purpose of the bio-art installation is to initiate a co-creation process between the animal and human spectators. For instance, in case the animal is a bowerbird, spectators are invited to present various objects to the bird, which it may or may not use to decorate its bower. This process is iterated and recorded, preferably in parallel and independently for several animals, although at some point interactions between individual animals might also be added to the mix, given that, for instance, bowerbirds tend to steal decorations from each other’s bowers. As Picasso is said to have said: “good artists borrow, great artists steal.”

How will the bowers look like?

Will individual bowerbirds of the same species tend to converge on similar characteristics of decorations, in terms of quantities, shapes, colors and so on, despite independent co-creation trajectories? Or will there be wide variability?

A possible outcome is that, once left unchecked by natural constraints, the bower will develop into a Superbower, consisting of decorations that are supernormally stimulating to the bird’s and perhaps the human beholder’s eyes.

ARTIFICIAL NATURE at Verbeke Foundation, Belgium

(cancelled my participation due to prep for fellowship at KLI in Austria)

Bio-art tentoonstelling 23 mei 2009 – 15 november 2009

Art Orienté objet (F), Sjoerd Buisman

(NL), Peter De Cupere (B), Marta de Menezes (P), Frederik De Wilde (B), Bart

de Zutter (B), Griet Dobbels (B), Jef Faes (B), Idiots (NL), Theo Jansen (NL),

Wout Janssens (B), Reinier Lagendijk (NL), Sjef Meijman (NL), Zjos Meyvis (B),

Desmond Morris (UK), NCNP (Ni Christi, Ni Politici) (B), Zbigniew Oksiuta (PL),

Raphaël Opstaele (B), Ingo Botho Reize (D), Joris Ribbens (B), Tineke

Schuurmans (NL), Lieven Standaert (B), STARTEL (NL), Martin uit den Bogaard

(NL), René Van Corven (NL), Ronald van der Meijs (NL), Philippe Vandenberg

(B), Maarten vanden Eynde (B), Koen Vanmechelen (B), Jan Verpooten (B),

Vadim Vosters (B), Stan Wannet (NL), Evelyne Wood (CH).

Mondrianian Movement

|

|

|

|

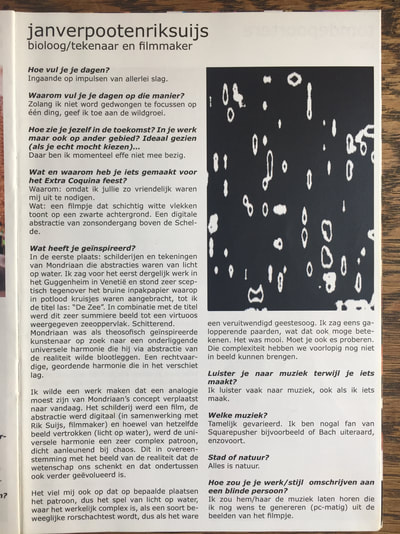

Mondrianian Movement is an installation of three simultaneously playing abstract video's, which I created with filmmaker Rik Suijs. The work is inspired by Pieter Mondriaan's series of highly abstract seascape paintings in which mere vertical and horizontal lines represent the wavy surface of the North Sea.

Some reflections

I like watching the movement of water reflections and I assume I am not the only one. Why do these dynamic patterns move us? One possible explanation is that they inadvertently resemble biological motion.

Detecting and having an attentional preference for biological motion is a highly conserved capacity shared among a wide range of animal taxa. This makes sense as it is crucial to evolutionary fitness: it modulates interactions with predators or prey, kin, mates or competitors.

A classic psychological study showed that even quite abstract and minimalist movements of geometric forms are perceived as "alive" if they move in a certain fashion.

Hence, perhaps we are naturally fascinated by and drawn to light reflected on a wavy water surface because it activates the 'agency detecting device' in our brain.

Exhibitions

¡Expo Coquina! and ¡Extra Coquina!, group shows, Fake Bar / Extra City, 2005, Antwerp.

An interview in the catalog of ¡Expo Coquina! provides some background information about the conceptualization of the work:

Some reflections

I like watching the movement of water reflections and I assume I am not the only one. Why do these dynamic patterns move us? One possible explanation is that they inadvertently resemble biological motion.

Detecting and having an attentional preference for biological motion is a highly conserved capacity shared among a wide range of animal taxa. This makes sense as it is crucial to evolutionary fitness: it modulates interactions with predators or prey, kin, mates or competitors.

A classic psychological study showed that even quite abstract and minimalist movements of geometric forms are perceived as "alive" if they move in a certain fashion.

Hence, perhaps we are naturally fascinated by and drawn to light reflected on a wavy water surface because it activates the 'agency detecting device' in our brain.

Exhibitions

¡Expo Coquina! and ¡Extra Coquina!, group shows, Fake Bar / Extra City, 2005, Antwerp.

An interview in the catalog of ¡Expo Coquina! provides some background information about the conceptualization of the work:

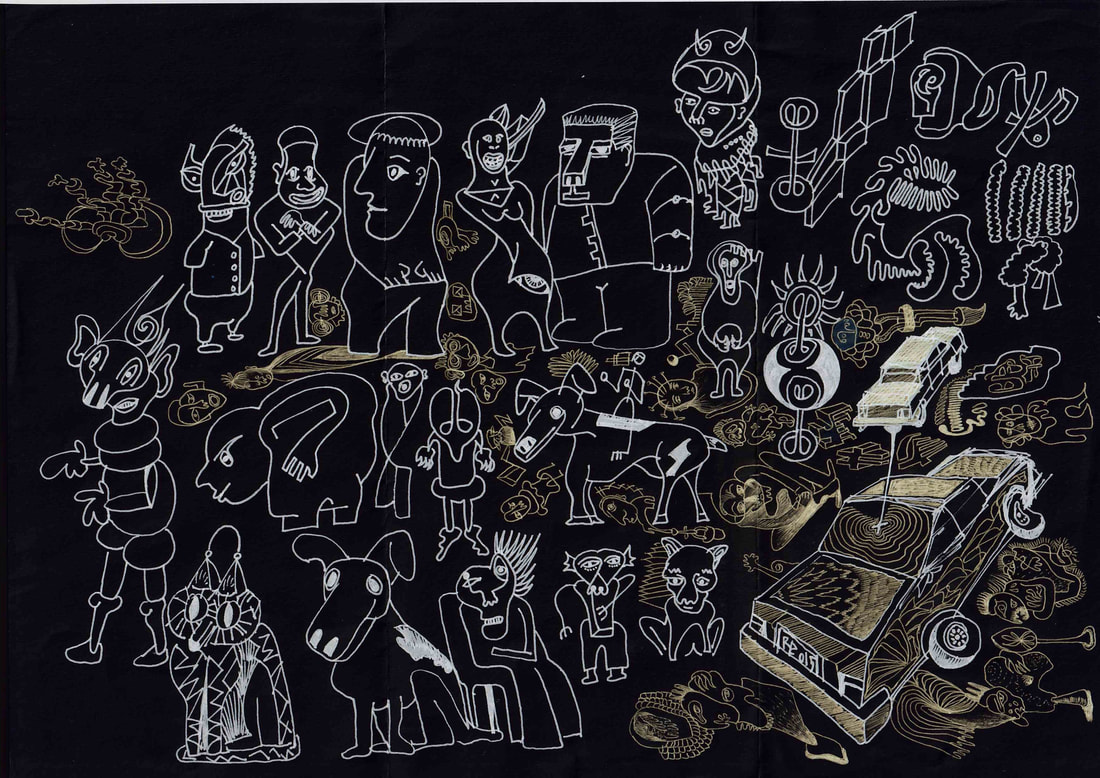

D(igital D)oodles

The more abstract doodles emerge from play with the pattern seeking brain